By Rachel Breitweser ’03

Not only is Sacramento-based artist Marcy Lichter ’53 Friedman passionate about creating art – beautifully bold portraiture – but she also is dedicated to sharing the benefits of art with those around her.

Friedman’s advocacy includes advancing the creative and philanthropic missions of numerous nonprofits. An avid art collector, she has loaned her personal collections to museums, and while on the California Arts Council, she strongly advocated for bringing art to public spaces.

She and her late husband, Morton Friedman, a prominent Sacramento businessman, lawyer and philanthropist, were key supporters of expanding Sacramento’s Crocker Museum. They spent a decade developing a new building that took the Crocker beyond a Victorian-era museum to an institution featuring world-class California arts, European master drawings and international ceramics. Friedman and her son, Mark Friedman, are now developing an art park fronting the museum.

“These types of institutions are powerful educational influences,” she said. “Museums aren’t static repositories of old stuff, but reflective of the values of a community – what our culture is and has been, and how to honor it.”

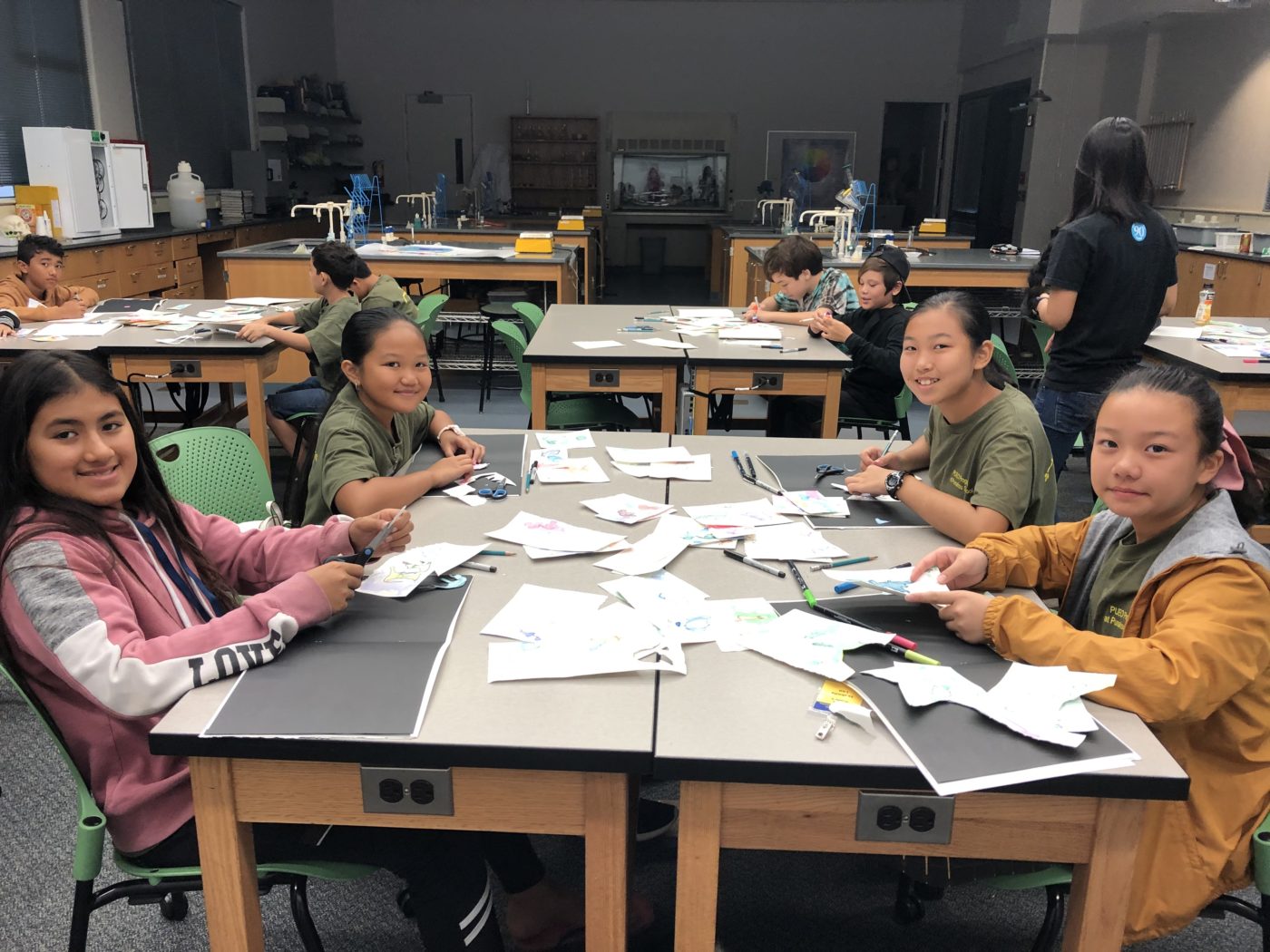

Recently, Friedman has influenced the lives of budding young creative minds at Punahou with her support of visiting artists.

Art class is where creativity is born, Friedman said, and not just for art. “When you open a child’s mind to creativity, they can also think about programming for computers or creating apps, because they can pull something out of their minds, and that is creativity,” she said. “It starts with encouraging the arts.”

This sentiment, along with a desire to show gratitude to Punahou, prompted her to establish the Marcine Lichter ’53 Friedman Endowed Fund for Visiting Artists, which allows distinguished artists in the visual arts, music, poetry, dance, performing arts and architecture to visit Punahou. Through her fund, POW! WOW! founder Jasper Wong and Native Hawaiian artist and illustrator Solomon Enos recently shared their talents and insights with students.

Friedman has fond memories of Punahou, where she attended from grade 2 to graduation. The Stanford graduate recalls her friendships, the quality of teachers, digging in the garden in third grade with Mr. Watanabe, and being called on by the theater department to paint a backdrop for a play. “Even at an age when I wasn’t terribly outgoing, there were people who recognized whatever latent skills or talents that were there and helped nourish them,” she said.

Friedman’s home is an extraordinary reflection of her curiosity and passion for creative expression – adorned with tribal works from Papua New Guinea and Africa. She’s continually refining her collection, filling in gaps in history or lending pieces to museums for others to enjoy. What she’s collected over time decorates every corner of her home, from the bedrooms to the kitchen. “It’s everywhere but the ceilings!” she said.

In addition to the bold expressiveness of the works, Friedman appreciates the cross-cultural ties, which show how human beings are far more alike than different. She has experienced ubiquitous connections during her travels around the world and values art as a way of tapping into universal feelings. “Artists are unafraid to approach emotion,” she said.

Friedman herself has used art to cope with difficult feelings. After a 40-year hiatus, she returned wholeheartedly to the craft with the impending passing of her late husband. “Art has a capacity to heal, and it was the bridge I walked on to cross the gap between the loss of a lifetime partner and resuming my life,” she said.