By Carlyn Tani ’69

When Ke’alohi Reppun ’99 entered Punahou in 1993, she wanted to study Hawaiian language but it wasn’t something that was offered in the Middle School. Later, she discovered that she couldn’t fit the Academy’s one Hawaiian language elective into her schedule. Reppun, who was raised on a kalo farm in Waiāhole, amid extended family, finally found the programs she was looking for at the University of Hawai’i, Hilo, where she earned a degree in Hawaiian Studies and Psychology. She went on to teach at Ke Kula ‘O Nāwahīokalani’ōpu’u Iki, a Hawaiian language immersion school in Kea’au. But Punahou was never far from her mind.

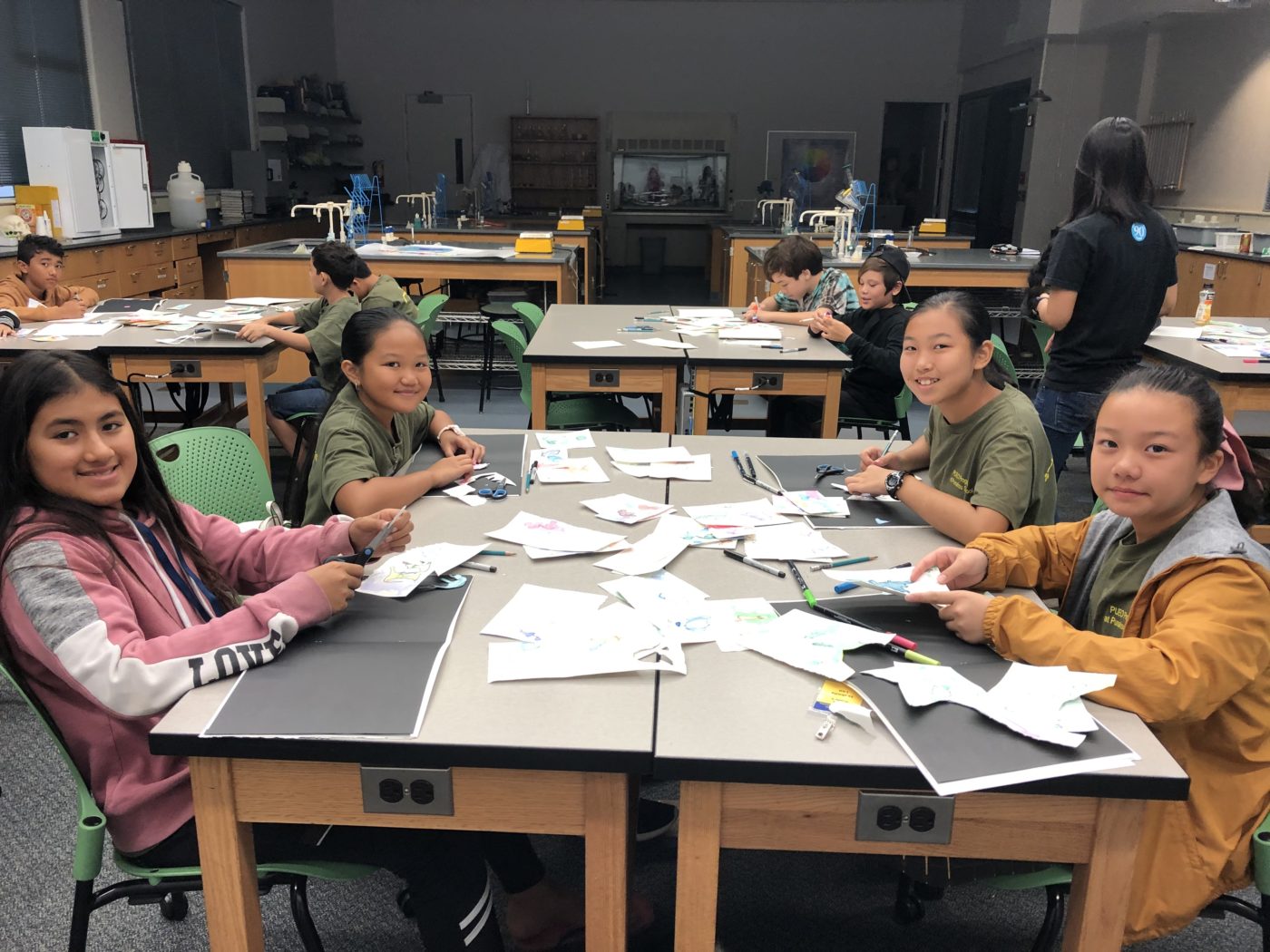

Reppun returned in 2013 to teach seventh-grade social studies, inspired by the changes she saw happening at the School under President Jim Scott ’70. Among his many achievements, Scott had articulated a compelling story of Punahou that embraced its Hawaiian roots, leading to important shifts in the curriculum. Today, Academy students can choose from five credit-bearing levels of Hawaiian language along with three electives in Hawaiian culture and Hawaiian ensemble music, while middle schoolers can take Hawaiian language in seventh and eighth grades (a second seventh-grade section was added this year). An after-school Hawaiian language immersion program is also open to students K – 3. Overall, more than 800 students in the Junior School and Academy participate in Hawaiian language and/or Hawaiian-focused studies.

During her first year teaching, Reppun decided to pilot a six-week course in Hawaiian language for faculty and staff. She was shocked by the response. “We had 50 people from all over campus coming together to learn Hawaiian,” she marvels. “And that’s when I realized that there’s a thirst and a hunger here for ‘ike Hawai’i – things Hawaiian, things of place, things of old and things of new. And that’s also when I decided to give this community what I had to offer.”

Reppun and Malia Ane ’72 currently serve as co-directors of Kuaihelani Learning Center, the hub of Hawaiian Studies at Punahou, which is housed in an airy, light-filled building at the center of Case Middle School. Together, Reppun and Ane are guiding a vital transformation in Punahou’s educational culture by supporting teachers who want to bring a Hawaiian perspective to their teaching. It’s not about adding new programs, Reppun emphasizes, but about creating a schoolwide culture that reconnects people to the ‘āina, the land.

“It’s a mindset that allows us to think about ‘āina, and along with that mindset comes language, history and mo’olelo, all of which connect us more strongly to the natural world,” she explains. Teachers and students are embracing this approach as a powerful fulcrum for learning. Whether it’s kids preparing to travel abroad or to a neighbor island, or learning to cultivate native plants on campus, ‘ike Hawai’i is coming into full bloom at Punahou.

KNOW YOUR HOME

A gaggle of rising seniors gathers outside Kuaihelani, chatting among themselves and jostling against one another. It’s the first day of orientation for the 50 students that will be traveling to either Iceland or China in the summer. “Aloha e nā haumāna,” says Ane, waving to the kids as she stands in front of the entryway. When they hesitate in responding, Ane chides them gently. “This is the first thing we should recognize when someone greets you,” she says, noting that it took a while for the students to focus their attention. “When you’re on your trip, you want to show respect because you don’t know the customs of that place. You have to be observant of everything.” She repeats her greeting and, this time, the students reply in unison: “Aloha e Kumu Ane.”

“ANY STUDENT WHO’S TRAVELING AND INTERACTING WITH ANOTHER CULTURE REPRESENTS THE LANDS THEY COME FROM, AND THEY HAVE TO BE ABLE TO SHARE THAT KNOWLEDGE WITH OTHERS. IT’S CRITICAL TO BEING A GLOBAL CITIZEN.” CHAI REDDY, DIRECTOR OF WO INTERNATIONAL CENTER”

CHAI REDDY, DIRECTOR OF WO INTERNATIONAL CENTER

They enter Kuaihelani, where Ane shares the story of the building’s namesake, Abigail Kuaihelani Campbell, and how she helped gather thousands of women’s signatures to protest the 1898 annexation of Hawai’i. Kuaihelani is also the name of a gathering place for the akua, or gods, she explains. Ane points to the timeline of Hawaiian history above them on the walls, and describes how Governor Boki and Liliha, with counsel from Queen Ka’ahumanu, gave the original gift of spring-laden lands to the School. “This is the place we come from; there’s so much history here,” Ane says. “And it’s our kuleana to learn as much as we can, because we were given this gift and we need to be grateful.”

She then turns to teaching the students an oli komo, written by Pal Eldredge ’64, celebrating the lands of Punahou. The students tentatively repeat the first couple lines. “You’re chanting for all of us who are home. Again! Stronger!” she urges. Their voices gain in volume and confidence. “Now, people are going to expect that you can dance, too. And this is not Merrie Monarch, so everyone’s going to do it,” she calls out. Breaking up into lines, the students dive into learning the hula “Aia i Punahou.” They’re engaged, laughing at their own mistakes amid Ane’s cheery exhortations.

Gordon Asato ’19, who entered Punahou in ninth grade, says the lessons he learned at Kuaihelani gave him “a sense of belonging to Punahou and to Hawaiian culture.” His group traveled to Iceland to study sustainability, and Asato feels that knowing the oli “allowed me to take pride in being from Hawai’i and created a deeper connection to the land here and in Iceland.” Mei Lee ’19, who journeyed to China, reflects that “wherever we went, people shared with us their trade or specialty, and it was really great to have something to share with them in return.” In Li Jiang province, the group visited a noted artisan, who crafts traditional Chinese instruments. He taught the students how to make their own bamboo flute and to play a few simple tunes. After the workshop, the students performed the mele they had learned to express their appreciation. As they finished each piece, the artist would cry out, “More! More!”

“Any student who’s traveling and interacting with another culture represents the lands they come from,” says Chai Reddy, director of Wo International Center. “And they have to be able to share that knowledge with others. It’s critical to being a global citizen.” Hawaiian Studies is content-based, he points out, “so it’s important that we practice it in all the work we do as teachers” to encourage students’ cultural fluency. Reddy, who’s seen a rising awareness of Hawaiian Studies across campus, credits Scott with clearing the path: “Starting with Jim and permeating outward, Hawaiian Studies has come to the foreground.”

THE GIFT OF THE LAND

Jim Scott returned to Punahou as its president in 1994, after serving nearly a decade as headmaster at Catlin Gabel School in Portland, Oregon. Early in his tenure, John DeFries ’69 paid him a visit and tossed out a provocative idea. “He sat here in this office,” Scott recalls, gesturing around his spacious, well-ordered suite in Sullivan Administration Building. “And he said, ‘We always knew about the missionary side, but I always wondered why we didn’t know about the Hawaiian side.'” DeFries went on to describe the two gifts that define Punahou – the vision of a school from Protestant missionaries and the gift of land from Hawaiian ali’i. “His exact words were the duality of the two gifts,” says Scott, noting that duality implies tension. “But that also means that Punahou is called to two different lineages, through history, culture, tradition and values. And when we embrace that tension and that complexity, we honor both sides.”

Scott soon crafted his own compelling narrative around the two gifts, which gradually transformed how the School views its own history and aims. He also gathered the resources, financial and human, to explore how this new narrative might enrich teaching and learning. With help from the Campbell family, he established Kuaihelani Learning Center, headed by the late Hattie Eldredge ’66 Phillips from 2005 to 2010, opening the way to curricular integration and innovation. Through the Aims of a Punahou Education, which articulate the School’s strategic vision, he affirmed Hawaiian values and culture as integral to student learning. Punahou already had been moving in that direction, through the third-grade experience, Chapel program, May Day and Holokū, but the Aims of a Punahou Education, Scott says, “explicitly give us the authority and permission to build upon that, to ground our students in the history of the lands and connect them to a shared Hawaiian past.”

“THE AIMS OF A PUNAHOU EDUCATION EXPLICITLY GIVE US PERMISSION TO GROUND OUR STUDENTS IN THE HISTORY OF THE LANDS AND CONNECT THEM TO A SHARED HAWAIIAN PAST.”

JIM SCOTT ’70, PRESIDENT

Last school year, fifth-graders journeyed to Hawai’i Island for a three-day visit that culminated in a night hike through Hawai’i Volcanoes National Park. Standing at the rim of Halema’uma’u crater, under the starlit skies, they performed oli and hula dedicated to Pelehonuamea, goddess of the volcano. Outdoor Education faculty had worked hand-in-hand with Kuaihelani to design the student experience (which currently is being reformulated due to the recent eruption). Before the trip, Ane taught the children a selection of oli and hula along with mo’olelo of the place. At Volcano, students prepared to walk the route during the day to familiarize themselves with its contours. But first, Reppun advised them on protocol. “I talked about the different wao, or land divisions,” she says. “You have wao kanaka, where kanaka live; wao nahele, where the forests are; and wao akua, where the akua live.” Moving through the different wao requires that one’s behavior changes accordingly. In the wao nahele, she told the students, “You have to watch – you have to watch your trail, you have to pay attention to the wind and the rain and the birds. When you move to the wao akua, it becomes a spiritual space and your behavior should reflect that reverence and respect.”

The night of the performance, the students hiked silently along the trail, which was lit only by the evening sky. “We were under the stars, we could see the Milky Way and, in the distance, we could see the glowing lava,” recalls Andy Nelson, Outdoor Education teacher. At the rim’s edge, the group lined up and opened with oli komo. Then, with Ane accompanying on ipu, they began to dance “Aia la o Pele,” sending their kahea, or call, into the vast expanse below. When they finished the performance, the clouds lifted, the lava’s glow intensified and smoke began to pour from the crater. Pele had given her pane, or answer. The children observed the phenomenon in awed silence. It wasn’t until they returned to camp that the students broke into excited gasps of astonishment. Reppun says: “They were saying, ‘Oh my God – did you see that?’ so they had obviously understood the lesson of the wao akua, and they knew what was happening.”

Back on campus, students are understanding that the lands of Punahou are not only a powerful springboard for learning but a fascinating map to Hawai’i’s history. In a clearing on the slopes of Rocky Hill, bordered by a dense thicket of haole koa, Academy geometry teacher John Chock ’01 checks on a row of spindly ‘ilima plants dotted with tiny, yellow flowers. “We planted these last year,” he explains, plucking a fragrant blossom. “They’re very delicate so it takes about 90 of these to make one lei.” Chock, who also teaches a middle school elective and G-Term course called “E Lei Kau” that centers on the cultivation, harvesting and making of lei, is reviving a forgotten slice of history on this unlikely patch of earth.

Two years ago, middle school librarian Dita Ramler-Reppun ’70 sent him a mo’olelo written by Emma Ka’ilikapuolono Metcalf Beckley Nākuina, who had a distinguished career in the 19th century as a judge, water-rights commissioner and curator. (She also was among the first Hawaiian students to attend Punahou, in 1852.) The mo’olelo recounted how a pair of twins, Kauawa’ahila and Kauaki’owao, were exiled from Ka’ala and forced to take refuge at the base of Pu’u o Mānoa, or Rocky Hill. Nākuina listed the plants the twins relied upon for sustenance: ‘ilima, ‘āheahea, pōpolo and mānienie ‘aki’aki, the latter being “the medicinal grass of olden times used for exorcising spirits.”

Guided by the mo’olelo and by support from Kuaihelani, Chock wanted to find out if these plants could thrive on Rocky Hill today. The Hill’s surrounding base, which is one of the campus’ last untouched spaces, retains its original, porous soil. His students pored over elevation maps and rainfall data to identify the plant species or subspecies that might be suited to the area. “And when we tried three of the four plants that Nakuina listed,” Chock says, “we found that they immediately flourished.” The ‘āheahea the class planted last year now reaches 8 feet tall. Without the use of fertilizer, pesticides or irrigation, some plantings haven’t survived, and his classes continue to experiment with cultivars raised at the plant nursery atop Rocky Hill.

Someday, Chock envisions that the hillside can return to its original state as dry, low-elevation shrubland, a native ecosystem that is virtually extinct on O’ahu. Meanwhile, the plants have already found a prized, new role in his lei-making classes. The tradition of lei, Chock explains, is more than an exchange between people but represents a cherished gift from the land. He gives the example that “when (Royal Hawaiian Bandmaster) Aaron Mahi came to campus, we were able to welcome him with an ‘ilima lei the students made from flowers grown at Punahou rather than a lei we bought at the store.” A new lei garden has recently been planted adjacent to the Sidney and Minnie Kosasa Community for Grades 2 – 5, putting culturally appropriate plants within easy reach of students in the third-grade Hawaiian Studies curriculum and others.

Moanike’ala Wong ’19, one of the student leaders of last year’s “E Lei Kau” G-Term is a hula dancer who comes from a family of lei-makers. Over the three-day session, she helped other students gather ferns and greens from around campus and guided them in making three different styles of lei: wili, haku and kui. “Punahou is not really known as a Hawaiian school,” she notes, “but the idea that we were able to practice values like mālama ‘āina, laulima and aloha through lei-making was really important. I personally feel a connection to ‘āina-based learning, which is about cultivating the land and our relationships to one another, so this class helped students understand that in a meaningful way.”

A PRIVILEGE AND A RESPONSIBILITY

Alongside bringing Hawaiian culture into classes, Kuaihelani is also reshaping the School’s role in the community. The Center reaches out to parents, alumni and the broader public through sponsorship of a range of programs and exhibits. Recent events have featured the achievements of Hōkūle’a’s Worldwide Voyage; the historical context that led Henry ‘Ōpūkaha’ia to inspire the missionary migration to Hawai’i; the Ali’i Letters from Mission Houses Museum; and a reexamination of Kalaupapa, the former Moloka’i colony where leprosy victims were forced to live in desperate isolation. In 2015, at the Gates Family Science Workshop, artist-in-residence Meleanna Aluli Meyer ’74 displayed the thought-provoking, 24-foot mural, “‘Āina Aloha,” which she had painted with five other Hawaiian artists. More than 1,300 K – 12 students viewed the double-sided mural, which sprang from the desire to “paint away” the historical pain borne by Native Hawaiians. On one side, the mural depicts a panorama of abundance: blissful human faces, kalo, ‘umeke and fresh water. The opposite side exposes the underlying trauma in a dramatic unfolding of seething, fractured images. Fifty alumni and parents came to the public viewing, engaging in a candid exchange that raised complex, often conflicting, emotions. “I was happy that the parents and alumni expressed themselves so honestly,” Meyer says. “We can’t go back in history but we can go forward, armed with the truth. And Punahou, I feel, is moving slowly and purposefully toward that truth.”

Seated in her office at Kuaihelani, Ke’alohi Reppun talks about kuleana, a term that implies both privilege and responsibility. “The fact that Punahou students have so much privilege tells me we have an even greater responsibility to ‘auamo, to carry, ‘ike Hawai’i in perpetuating culture, history and storytelling. We have a kuleana to this place and to our people to do good,” she says, citing the intractable environmental and social issues that beset the Islands today. “We also have to develop cultural fluency within our haumāna so that, no matter where they go in the world, they have eyes that see culture, that enable them to be authentically and respectfully responsible.” She leans forward in her chair to make a final, impassioned point. “Punahou has the power to influence the way that other institutions approach education. If we make ‘ike Hawai’i a priority, and if we are successful, then it will give institutions permission to go down the path of ‘ike Hawai’i, making it a learning priority for all our children in Hawaiʻi.” She adds, with a smile. “That’s grand, big-picture stuff. But I honestly believe that that is the potential and the kuleana that Punahou has in our greater society of Hawai’i.”

At the end of Nākuina’s mo’olelo, she notes that the shrubs and bushes that once nourished the heavenly twins have disappeared. “Old natives say there is now no inducement for the gentle rain of Ka Uaki’owao and Ka Uawa’ahila to visit those bare hills and plains, as they would find no food there.” The new plantings of ‘āheahea and ʻilima on Rocky Hill represent a small step toward the larger purpose of teaching students their kuleana. In the same way, ‘ike Hawai’i is slowly taking root across Punahou. As teachers weave Hawaiian culture into their classes, they begin to transform the culture of the School, bringing to life the enduring mo’olelo of the two gifts.

Carlyn Tani ’69 is a Honolulu-based freelance writer and parent of Bobby Foley ’06.

KAPUNAHOU

In “Kapunahou” – a commemorative book published in celebration of the School’s 175th anniversary – Jim Scott narrates the historic origins of the Hawaiian gift of land that laid the foundation for an educational vision of Protestant missionaries at the site.

Early in my tenure, I came to appreciate that the School’s singular mission and vision stem from two historic gifts that set the foundation for today: the gift of land from Hawaiian ali’i and the gift of an educational vision from Protestant missionaries. Our New England heritage of scholarly achievement, coupled with our Hawaiian reverence for place, inspires a philosophy of educational renewal that thrives within a campus of timeless beauty.

Ancient Hawaiians prized the land of Kapunahou, nestled in the fertile ahupua’a of Mānoa, for the life-giving freshwater spring at its core. In 1795, King Kamehameha I awarded Kapunahou to his loyal chief Kame’eiamoku after the triumphant Battle of Nu’uanu. Kame’eiamoku later entrusted the lands to his son, Hoapili, who for 20 years resided in the vicinity of the spring. Kamehameha I was a frequent guest at Hoapili’s home and often walked the surrounding grounds.

From the time of Kamehameha I, control of all land in Hawai’i remained in the hands of the ruling chief; however, land inheritance for high-ranking chiefs like Hoapili was allowed. Hoapili in time gave Kapunahou to his daughter, Liliha, and her husband, Boki. In 1829, at the urging of ruling chief Queen Ka’ahumanu, an avid supporter of Christianity, the couple granted custody of Kapunahou to the Reverend Hiram Bingham, leader of the missionary community in Hawai’i. Liliha initially resisted the conveyance of land, but Boki proceeded with entrusting its custody to Bingham before departing on an expedition to the South Pacific. Ka’ahumanu served as konohiki, or landlord, for Kapunahou. She had a thatched house erected for herself near the spring and an adobe-and-thatch cottage for the Binghams near the present Old School Hall. Boki was lost in a disaster at sea and never returned, and Kapunahou remained under Bingham’s, and thus the Sandwich Island Mission’s, stewardship.

After the Mahele of 1848 instituted private land ownership, the American Board of Commissioners for Foreign Missions (ABCFM) sought written title to Kapunahou. John Papa I’i, a respected advisor to Kauikeaouli (Kamehameha III) and a member of the Land Commission, was among those who testitifed in favor of the mission, and in 1849 the Land Commission granted the title for Kapunahou to the ABCFM.

… Today Punahou educates 3,750 students from a broad cross-section of Hawai’i, all of whom experience the School’s dual legacy. Mālama ‘āina, caring for the Earth, affirms our appreciation for the original gift of land. As modern stewards of a wahi pana, land that is steeped in history, we have a responsibility to cultivate the natural and cultural resources of Kapunahou. The School’s focus on a revitalized campus centered on Kapunahou, combined with a renewed emphasis on Hawaiian culture and language, sustains our connection to Punahou’s Hawaiian origins.

A QUEEN’S HOMECOMING

By Catherine Black ’94

The late Fred Roster was a master sculptor and professor of art at the University of Hawai’i who passed away in December 2017. While his art was celebrated across the state, few knew of his interest in the fearless and iconoclastic figure of Ka’ahumanu, whose support of the Sandwich Island Mission made possible the eventual founding of Punahou School.

Spanning a period of nearly 20 years, Fred created a series of studies of Ka’ahumanu, beginning with a sculpted portrait commissioned by the State Foundation on Culture and the Arts that was installed at Ka’ahumanu Hale First Circuit Court. In the late 1990s, he created a 2-foot-high sculpture of her in clay and cast it in a durable gypsum cement with a patina finish similar to bronze, but his dream had always been for the figure to one day be cast in true bronze, an expensive and complex process. Fred brought her home in 1998 and she sat on his drafting table near the front door for 18 years, waiting for the appropriate moment to move on.

During Punahou’s 175th anniversary year, the stories and spirits of the past were called back to campus in many ways, including a pictorial timeline of Hawaiian ali’i in Kuaihelani Learning Center. Fred’s wife, Lynette, was a librarian in Bishop Learning Center at the time and, while looking at these portraits one day, she had an epiphany: “The idea to gift this sculpture to Punahou came as a simple and striking realization. It was the right time for Ka’ahumanu to return home to Kapunahou!”

This clarity came at a time of great turmoil at home, as Fred was rushed to the emergency room with stroke-like symptoms that spring. Lynette gave notice to Punahou so that she could care for him and, that summer, he was diagnosed with malignant brain cancer. “Our focus was on his treatment, and yet the thought of gifting Ka’ahumanu brought lightness and hope to our days,” she remembers. There was a feeling of excitement as the family came together to plan the many steps to realize this vision, beginning with a letter to the School.

In the letter, Fred wrote, “My wife and I would like to gift this sculpture of Ka’ahumanu to Punahou School. We cannot think of a more appropriate home for her. From a spiritual and historical perspective, Ka’ahumanu should be remembered as Kuhina Nui and wife of Kamehameha I. She embraced Christianity and literacy for her people. Her influence is shown in Liliha and Boki’s gift of the land to the missionaries who founded Punahou School. Ka’ahumanu built her hale near the original Kapunahou spring. My wife Lynette culminated her career as a school librarian at Punahou at the time of the 175th celebrations, when it became apparent that Punahou’s history and thread began with Ka’ahumanu.”

Conversations were initiated with Malia Ane ’72 and Ke’alohi Reppun ’99 about curricular uses for the statue in Kuaihelani. Fred’s son, Cade ’91, and daughter-in-law, Waileia Davis ’86 Roster, worked with the Office of Institutional Advancement to handle logistics of the gift. Longtime arts patron Sharon Twigg-Smith, with help from Punahou Trustee Wendy Crabb, raised the funds for the bronze casting, visiting Fred just days before he died to give him the news confirming its bronzing. Artists John Koga ’82 and Lawrence Seward handled her crating to a foundry in Los Angeles where she was molded, cast and finished with a beautiful patina. Ka’ahumanu returned to Hawai’i in her specially built crate and was delivered by Koga to Kuaihelani this past summer.

Ane and Reppun plan to use Ka’ahumanu as a teaching tool in the Hawaiian Studies curriculum this year – a powerful physical presence to accompany the stories of Hawai’i that are interwoven with the story of Punahou.

“His dream finally did come true,” reflected Lynette with emotion. As Fred noted at the end of his letter, “That Ka’ahumanu has come home to Kapunahou is quite remarkable. Mahalo nui.”