By Cynthia Wessendorf

In the summer of 1969, a group of 27 Japanese teenagers dressed in formal dark suits and white dresses touched down in balmy Honolulu. Clutching lei and waving signs with “Aloha” written on them were their Punahou counterparts and host families, welcoming the visitors from the Keio schools for six weeks of English study and cultural immersion.

Seventeen years after normal diplomatic relations had been reestablished between the United States and Japan, the group’s arrival marked the official start of the Pan Pacific Program.

Brainchild of Siegfried Ramler, who established the Foundation for Study in Hawai’i and Abroad, precursor of today’s Wo International Center, the Pan Pacific exchange launched decades of travel, homestays, learning and friendships between Punahou students and their cohorts through Asia, the Pacific Islands, Central America, Africa and Europe.

While travel offers a window into other cultures and has been core to the Center’s global education mission, evolving initiatives focused on building empathy, navigating diversity, and working together to solve common problems have grown in importance and visibility. The 25th anniversary of the Wo International Center is an occasion to look back at some of the people and ideas that shaped its foundation, and those that are moving it forward.

Becoming a Global Citizen

Siegfried Ramler’s early life reads like a novel, including the grim parts: Escaped Austria via kindertransport during the Nazi occupation. Survived the World War II London blitz. Traveled to Germany to work as a simultaneous interpreter at the Nuremberg trials. Married court reporter Pi’ilani Ahuna and moved to her native Hawai’i in 1949.

Quickly hired by Punahou as a French and German instructor, Ramler was the ideal person to translate international perspectives and cooperation into formal programming. “Bring the classroom out into the world … and get the world into the classroom,” is how he described his educational philosophy.

After decades expanding the Pan Pacific Program from a single partnership with the Keio schools in Tokyo to a far-reaching network, Ramler hatched plans to bring the exchange program, guest lecturers and extracurricular language learning under one roof. By 1991, as construction of a physical home was becoming a reality, Ramler described its overarching goals in a memo:

“Considering the rapid pace of change throughout the world, the Wo International Center’s mission is to equip students with the ethical and intellectual qualities to become productive members of society and to deal with the many challenges facing our world.”

While these words still ring true, they lack the urgency that today’s staggering problems require. As job displacement from automation, climate change, massive refugee migration and xenophobia strain communities across the world, the goal of becoming a “global citizen” moves far beyond a high-minded ideal to become a crucial skill set.

But how do you help students make sense of the complex web of social, economic, environmental and political forces? How do you get them to think beyond their own self-interest and empathize with others? How can you trigger reflection about who they are and what they stand for?

Global education offers a framework for personal growth and a more generous, broad-minded approach to understanding perspectives and tackling problems. Programs championed by the Wo International Center, as well as by teachers and administrators throughout the School’s history, literally bring together students across the globe to learn and share solutions.

From exposure to different languages and cultures in Kindergarten through grade 5; middle-school exchanges with partners in Japan, China and Sweden; or Academy Capstone expeditions to Alaska, Bhutan and New Zealand, the learning experience starts with an understanding of themselves and their place in the world.

“We want students to look outward, but it’s important to look inward first,” says Chai Reddy, director of Wo International Center. “You can’t really be a good global citizen until you have an appreciation for where you come from and have those values of home ingrained.”

The next step is developing the skills to live with diversity in all its manifestations, whether cultural, linguistic, socioeconomic, gender, sexual orientation or anything else. Being a global citizen is not just locating the Amazon River on a map, explains Reddy, but about the values you have and how you practice them.

While diversity can be found anywhere, on the other side of the island or the world, global citizenship is about the willingness to be collaborative and empathetic, explains Reddy. “Can you coexist with those differences or can you only exist in a community that’s homogenous? We want to prepare our students to thrive in communities that are not homogeneous.”

Travel with a Purpose

When Wo International Center opened its doors in 1993, it was the country’s only international institution of its kind at the high-school level. In the pre-internet age, its focus on promoting cross-cultural fluency – understanding other people, cultures and languages – usually meant getting on a plane and going to your destination.

Hope Kuo Staab built on Ramler’s work to further open up the world for students. Having grown up in South Korea, Samoa and Fiji, her early life fueled a passion for exploring cultures and languages. During her tenure as co-director of the Center beginning in 1995 and director in 1998 – a position she held for 15 years – the Center forged new partnerships with schools in China, Japan, Costa Rica, Ghana and many other countries.

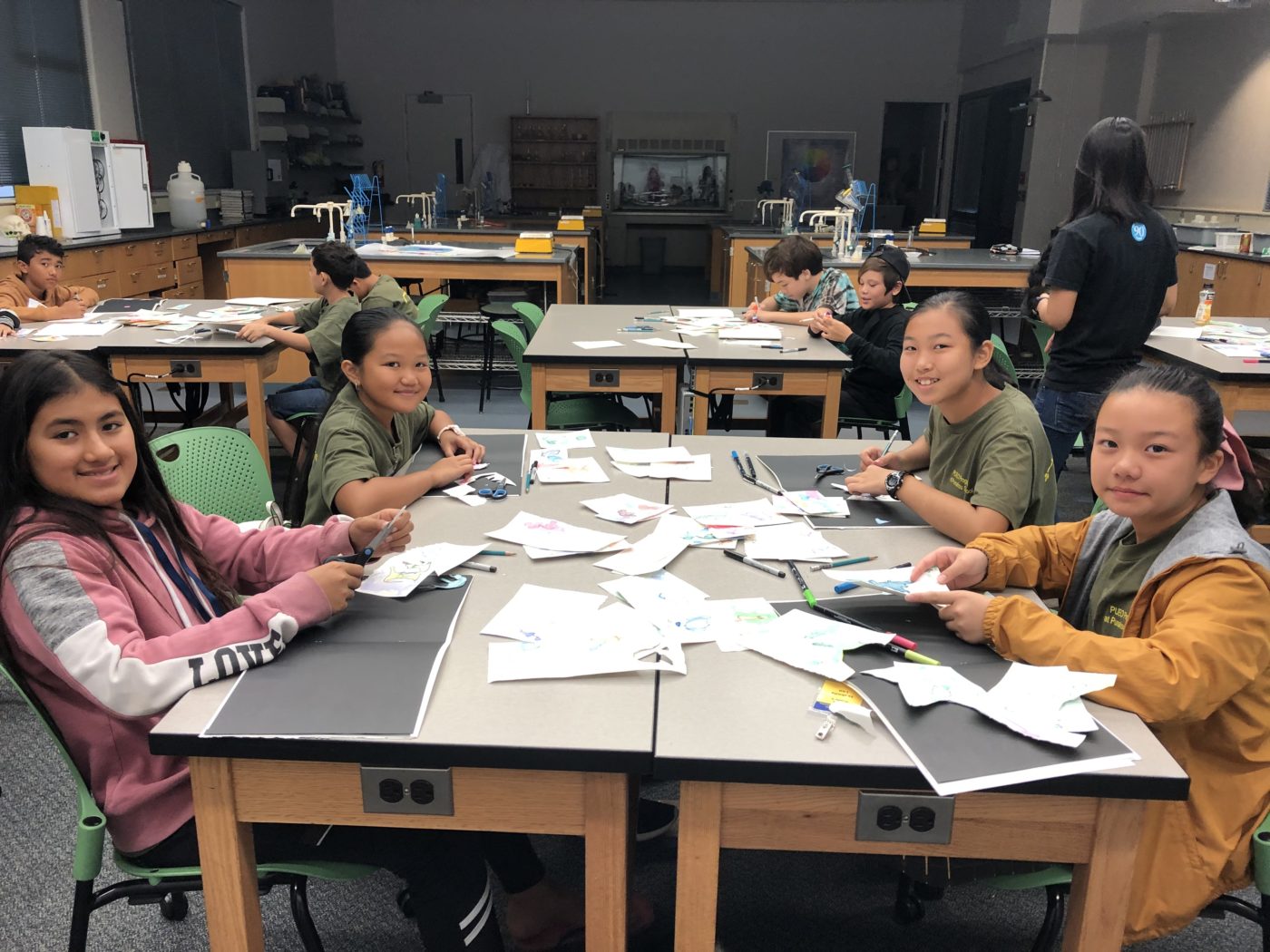

The direction of the Center’s programming shifted in 2004 when a group of Punahou students traveled to Baojing, a remote village in China’s mountainous Hunan Province, to teach English at the Minority Middle School. The recurring trip aimed to help the host students prepare for grueling college entrance exams, while also practicing Mandarin and tai chi on the side.

“In her prolific career, Hope was preaching that the purpose isn’t to go out and be a tourist, but to deeply understand communities and do meaningful work,” recalls Dr. Emily McCarren, Academy principal and former director of the Center. “Even in our trips that might look like a traditional exchange program, there’s still a lot of thought about how we live that aspiration.”

In 2010, Staab led the launch of the Student Global Leadership Institute, which gathers students from around the world to collaborate on pressing issues and form lasting cohorts. Hosted on the Punahou campus, and now also at Oakridge International School in Hyderabad, India, young leaders study topics such as conservation, equity, peace and energy.

Under current director Chai Reddy’s leadership, the summer Capstone courses have developed into rich, interdisciplinary experiences that tap faculty from math, social studies, English, foreign languages, science and the Punahou archives. These travel opportunities fulfill students’ Social Studies graduation requirement as they explore communities outside of tourist attractions, and often far from their own comfort zones.

The trips are carefully designed to focus on service, self-understanding and cultural awareness. Students not only share Hawai’i’s culture, but also exchange ideas about how to protect the environment and other concerns. The format pushes against “the Superman effect” that many service-oriented youth organizations inadvertently promote.

“You have to be very mindful that students don’t think they’re going someplace to help out for a couple of weeks, and then they leave and they’ve saved the day,” cautions Reddy. “We need to make sure we have something to share.”

For many travelers, the three weeks are some of the most momentous of their young lives. Steffany Nguyen ’18 was left speechless when a tribal elder in Juneau told the group that everyone matters and everyone is loved. “That’s not something that we are often told in our society,” she reports. “The trip helped me think about my life goals, and how I want to impact the community I live in. Knowing that I have a purpose in life really helped me develop this sense of self-confidence for my senior year and to be happy no matter where I end up going to college.”

Cultivating Empathy

Despite campus buzz about interesting travel opportunities, only a small fraction of students actually participate each year. But if global citizenship is not just a travel experience but also a mindset, then the essential mental, social and emotional skills can be practiced anywhere.

“An important question is, can you be a global citizen and never have left this island?” asks McCarren. “And, yes, you totally can, because global citizenship is not just about collecting stamps in your passport, but trying to understand different perspectives.”

For Eliza Leineweber ’92 Lathrop, Academy English faculty and K – 12 garden resource teacher, travel is a grounding mechanism. “We’re always looking outward, but it’s also important to look inward and know who you are and where you come from,” she says. “You cannot be empty and go out into the world and say ‘fill me.’ You have to have an understanding of self.”

Having participated in faculty trips to Morocco and Ghana in 2011, Tahiti and Rapa Nui in 2014, and New Zealand in 2015, Lathrop, a self-described homebody, finds that pushing herself out of routines and on to the road rekindles her values. She shares those values in her lessons, whether on Henry David Thoreau or cultivating crops.

With her students in the garden, for example, she might ask them to quietly observe, noticing how the sun changes positions and the light shifts as the winter season approaches. The goal is to get kids to slow down, reflect and become aware in ways that are empathic, not just to people, but to places as well.

“Becoming aware can help them connect with that world, especially as technology and globalization are pushing us toward an abstraction of our world,” Lathrop explains. “If you’re connected to everything, are you connected to anything at all?”

Over and over, empathy emerges as a defining mission of the Center and a desired outcome of its sponsored travels. Empathy is embedded in the Aims of a Punahou Education, along with compassion, collaboration and embracing diversity. But empathy is often lagging. For example, in reading fiction, Lathrop finds that students often fail to empathize with the characters and their lives. She describes a prevailing “if it doesn’t relate to me, I can’t be interested in it” attitude.

“That’s part of what global education teaches – if it doesn’t directly relate to you, it still relates to you. We have to challenge our students to see beyond the obvious and easy, to sit with the complex. We have to teach them skills that we don’t even know they need yet, but that’s the world they’re going into – things are going to be crazy complicated.”

Along with Luke Center for Public Service, Hawaiian Studies at Kuaihelani Learning Center and campus makerspaces, the Wo International Center is part of a network of learning centers that support the new K – 12 Learning Commons. McCarren sees the role of the centers growing in importance.

“Historically we’ve had a core academic curriculum and all these centers that provide experiences around the margins. But the centers really help transform the core academic experiences,” notes McCarren.

Currently, the Wo International Center offers an array of programs. For elementary grades, the Center offers after-school Hawaiian, Japanese and Mandarin immersion experiences, and introductory classes in French and Spanish. The Center’s faculty and staff work with teachers across grade levels to provide language and cultural lessons. They also handle travel planning and logistics for 200 students, as well as international excursions for educators. The Center hosts leadership institutes and serves as campus ambassador for visiting guests. Recently, the Year Abroad at Punahou program has been resurrected, and the Pan Pacific Program will relaunch with Keio schools to be a more collaborative experience.

Beyond filling the gaps, the Center offers opportunities for students to develop essential soft skills, including empathizing, communicating across cultures, and developing a global mindset – tools to better assess risks and rewards, weigh human and environmental impacts of projects and innovations, and make wise, humane decisions as they build careers in a changing world.

An Enduring Partnership

The year 2018 marks 50 years of collaboration between the Keio schools and the early incarnation of the Wo International Center, the Foundation for Study in Hawai’i and Abroad. To celebrate, the Punahou Symphony Orchestra, Chorale and the boys volleyball team will travel to Tokyo during spring break for musical performances, games and cultural sharing.

The Keio schools, which span the elementary grades to the university level, were founded by educational innovator Yukichi Fukuzawa. His travels in America and Europe in the early 1860s shaped a philosophy that advocated independence and jitsugaku, or empirical science.

As luck would have it – at a fortunate location at the crossroads of East and West – Fukuzawa visited Punahou (then Oahu College) at the start of his journeys, along with the noted translator and seaman Nakahama “John” Manjiro and Katsu Kaishu, captain of the ocean vessel Kanrin Maru. Japanese language faculty Naomi Hirano-Omizo and retired Japanese faculty Hiromi Peterson translated the captain’s travel diary. In one passage, he describes the group visiting campus on the evening of May 24, 1860, to watch a student performance of singing and oration, an event that left a lasting impression:

“That ceremony was quite unusual … The audience was composed of young and old, men and women, and rich and poor, with no discrimination. The queen already attended the night before, but wished to come again … The audience did not become bored. Moreover, they learned a great variety of (truths) as the speakers tried their best to explain their thoughts clearly to their audience. Both sides benefitted from these presentations.”

Days later, the Kanrin Maru sailed for Uraga, Japan, leaving behind the seeds of a vibrant, cross-cultural partnership that lives on today.

Global Programming Through the Years

1841

Latin and Greek are offered to Punahou’s founding class.

1860

A Japanese delegation stops in Honolulu and attends Punahou students’ rhetorical exercises; among the group is Yukichi Fukuzawa, founder of Keio University in Tokyo.

1863

Hawaiian language is a required class and utilizes texts that existed at that time, including one written by W.D. Alexander of Punahou.

1867

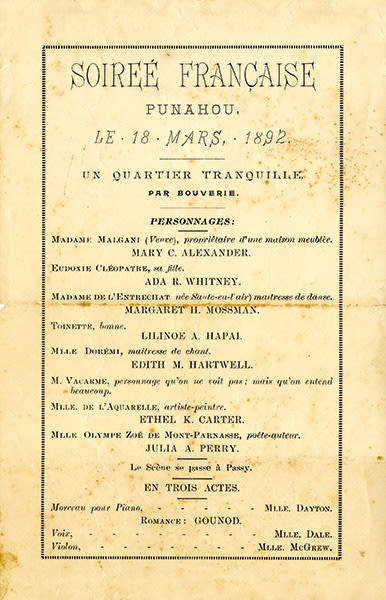

While French language classes were offered to students for a small fee in 1858, both French and German are incorporated into the curriculum without cost in 1867.

1883

Sun Yat-Sen enters Punahou (then Oahu College) under the name Tai Cheong. The future “father of the Chinese Revolution” embraces democratic and Protestant ideas that fuel his political movement.

1928

Over 300 delegates gather on the Punahou campus for the first Pan-Pacific Women’s Conference, a 10-day event led by social worker and political activist Jane Addams to raise cross-cultural understanding.

1938

A group of seven Punahou and Kamehameha students and faculty member Bayne Beauchamp travel via ocean liner and steamship to Alaska. They journey along the Yukon River to the Bering Sea, filming and photographing life in villages along the route. Beauchamp organized at least two earlier summer expeditions in 1932 and 1934 to the Far North.

1940

Spanish is first offered as an elective.

1944

The most popular language combination is two years of Latin and two years of French or Spanish; a World War II moratorium on German persists until 1951.

1947

Frank Belding, Punahou director of athletics and social studies teacher, leads 37 boys on an 11-week summer camping trip across America. The 12- to 16-year olds travel 11,000 miles, tour 14 national parks and seven national forests, and traverse 30 of the existing 48 states, with stops in Mexico and Canada.

1951

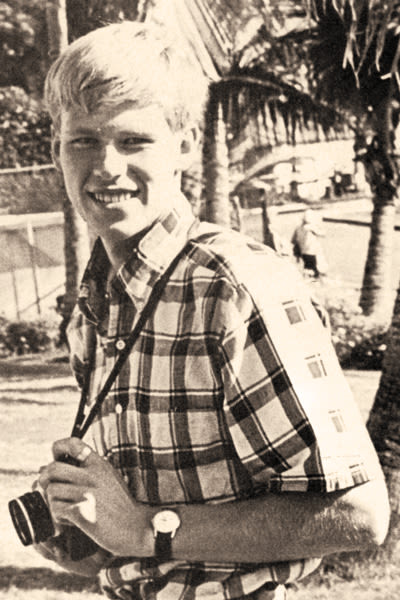

Siegfried Ramler is hired by Punahou to teach French and German language and literature; he soon becomes head of the Foreign Language Department.

1959

The Pan Am Boeing 707 begins flying to Hawai’i, opening up swifter, more affordable travel.

Japanese is added to the regular course schedule, after first being offered as an elective in 1943; Russian is offered for the next decade, ending in 1968.

Language labs are added to support Language curriculum.

1960

A strong focus on European languages prevails, with students encouraged to take six-year sequences of French, German or Spanish, combined with two years of Russian or Japanese as electives. Alternately, two years of Latin, followed by four years of a European language in the Academy is another popular sequence.

1966

Raimo Alhoke, an international student from Turku, Finland, joins the Class of 1967 for one year at Punahou. His experience was sponsored by the Punahou International Relations Club, whose focus, as stated in the 1967 Oahuan was to create “a wider comprehension of the meaning of ‘international.'”

1967

Chinese (Mandarin) is first offered in 1967 with the help of a Carnegie grant.

1969

Foundation for Study in Hawai’i and Abroad is founded by Siegfried Ramler, who serves as executive director until 1990. The foundation’s signature exchange program, the Pan Pacific Program, continues today.

Following a partnership initiated in 1968, the first group of 27 students from Keio schools arrives in Honolulu for six weeks of cultural immersion.

1970

Pan Pacific Program quickly grows to 26 Hawai’i students traveling to Tokyo, while 40 students visit Punahou from Japan, Tahiti and Micronesia.

International students arrive from Finland and Japan for study during the school year; more come from England, Germany, Norway, Sweden, Japan, Tibet, Denmark, Vietnam, India and Taiwan through the years.

1973

Pan Pacific Program sends its first outbound students to Tahiti for French language study and cultural immersion.

1975

Mandarin is formally launched in grades 7 – 8, while credit-bearing Academy classes begin the following year when linguist Hope Kuo Staab is hired.

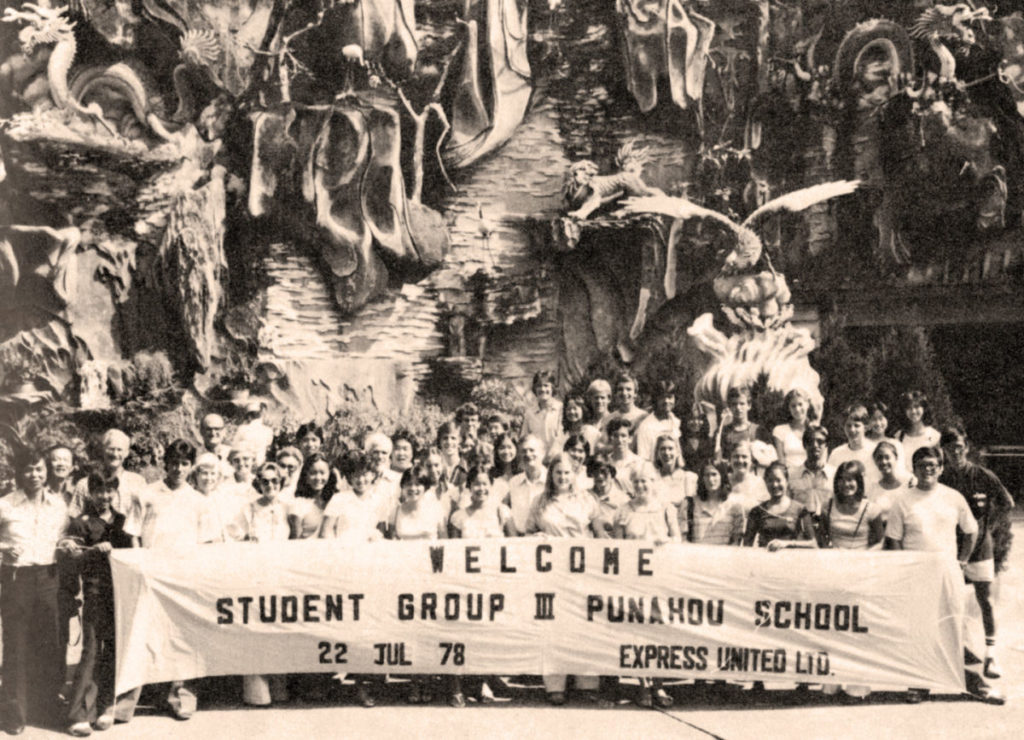

1978

Foundation for Study in Hawai’i and Abroad programming adds a two-week study tour to China for the first time, one year before normalization of diplomatic relations. Thirty-eight students travel to Canton, Hangchow, Shanghai and Peking.

1980

Hawaiian language classes are offered as enrichment in the Academy. Though interest is low, it is offered again in 1982 – 1983 as a regular, semester course on a biannual basis.

In 1986, Morita-Sony Media Center opens in Cooke Library.

1989

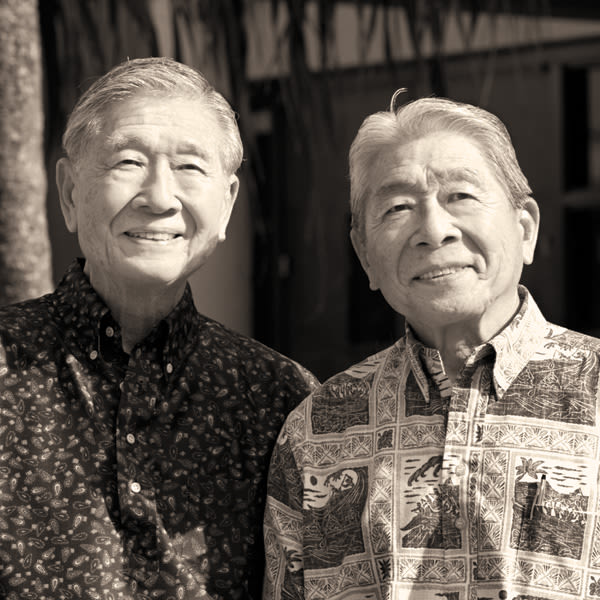

Robert Wo ’41 and James Wo ’43 pledge $3 million to fund international education and construction of a physical home for programming.

The K.J. Luke family provides an additional $1.5 million for Chinese studies, a community lecture series, and funding for state of the art projection equipment and a simultaneous interpretation system.

1990

Foundation for Study in Hawai’i and Abroad merges into the newly established Wo International Center.

Local architect John Hara ’57 is commissioned to design the new Center.

LACES (Language and Culture in the Elementary School) offers after-school experiences in French, Japanese, Mandarin and Spanish.

1991

The Luke Distinguished Lectures Series hosts an inaugural lecture by Winston Lord, ambassador to China. He is one of many political figures, journalists, diplomats and others invited to speak on campus in the 1990s.

After a 22-year absence, Russian language is re-introduced but classes are only offered for one year, ending in 1992.

1992

Construction begins on the Wo International Center.

1993

The completed Wo International Center, the first such center in secondary and elementary education in the United States, is dedicated on May 7; John Young donates a prized collection of art and artifacts for display.

Language experiences in Kindergarten – grade 5 include Japanese, Chinese, Hawaiian, German and French.

1994

The official Year at Punahou program for international students begins as seven students from Japan, Tibet, Germany and Cambodia are fully immersed in school life.

1995

Siegfried Ramler retires; Hope Kuo Staab and Bob Torrey are named as co-directors of the Center.

1996

The Center hosts 100 teachers from South Korea. A Japanese performing arts troupe visits, sharing traditional dance and music.

Punahou hosts the first-ever Pacific Basin Conference. Over 500 participants from 70 nations attend the regional gathering coordinated by organizations: NAIS, HAIS, PNAIS, CAIS and EARCOS.

1997

Travel courses are introduced to the official Academy curriculum with half-credit summer-school classes on China and Japan.

Hawaiian language is expanded into a sequence of two yearlong Academy courses, offered as electives.

1998

Hope Kuo Staab is appointed director; she heads the Center for 15 years, shaping it into a model of global education.

2001

Hawaiian language is phased in as a complete credit-bearing sequence that starts in seventh grade and continues to level five in the Academy, on par with Spanish, French, Mandarin and Japanese.

Punahou joins a consortium of independent schools participating in the Junior Year Abroad program.

2002

Academy Foreign Languages Department changes its name to Language Department.

2004

Students travel in the summer to rural Hunan Province in China to teach English at Baojing’s Minority Middle School, as well as study Mandarin; the service trip is repeated every other year.

2010

Student Global Leadership Institute launches, bringing high-school students from around the globe to the Punahou campus to problem-solve pressing issues; in 2015, a middle-school version begins on campus, and in 2016, Academy students travel to a partner school in India that hosts an extension of the Institute.

2011

Punahou teachers join a cohort from Phillips Exeter Academy to travel to Morocco and Ghana, two additions to an evolving list of summer opportunities offered to faculty.

Luke Center for Chinese Studies finds a permanent home at the Center.

2012

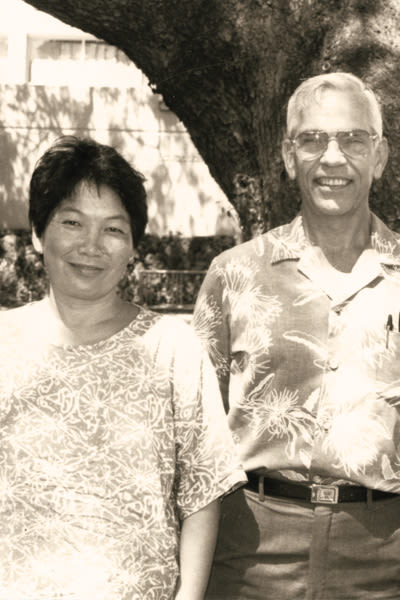

Emily McCarren is named director of Wo International Center. Photo: Current Director Chai Reddy with Emily McCarren.

Global Education Teacher Strand workshop launches to coincide with the Student Global Leadership Institute.

2013

The Center pilots an after-school Mandarin immersion program for elementary students; following its success, daily Japanese and Hawaiian classes are added, while LACES continues to offer French and Spanish once a week.

2015

Chai Reddy assumes the position of director of Wo International Center after McCarren is appointed Academy Principal.

Capstone International launches as an outbound version of the senior Social Studies graduation requirement.

2017

Academy introduces G-Term, including trips to Taipei and Cuba organized by the Center.

Capstone classes travel to the Arctic Circle, Bhutan, and New Zealand for study and service projects. Year Abroad at Punahou, first introduced in 1994, relaunches.

Cynthia Wessendorf is a freelance writer and editor, and the parent of a current Punahou student.