By Catherine Black ’94

When fourth-grade faculty Pamela Piper ’91 Fox began thinking about how she might develop an inquiry project around water, she knew she wanted to make the learning real for her students, both on campus and off. Thanks to her father, Steve Piper ’68, who served as head of Punahou’s Physical Plant for 25 years, she knew the fascinating story of the School’s spring, with its complex underground causeways and transformations over time.

So Fox consulted another person she knew was passionate about the waters of Ka Punahou, Ke’alohi Reppun ’99. As co-director of Kuaihelani Learning Center, the nucleus of Hawaiian Studies on campus, Reppun has a deep understanding of the spring’s ecological and cultural value. Her father, Paul ’68, and uncle Charlie ’65, are also well-known for their work to restore traditional kalo farming, which depends on healthy watersheds, and for their advocacy role in protecting Hawai’i’s water resources.

Reppun suggested that Fox spend a professional development day at her family’s farm, with its unique natural and man-made water systems: Waianu Stream nourishes numerous lo’i kalo through traditional ‘auwai irrigation ditches, as well as providing natural energy with a water wheel built by the Reppuns themselves. When Fox shared the idea with her fellow fourth-grade teachers, they enthusiastically jumped on board. Academy Science faculty Ali Dias ’89 Marumoto also joined them, on the lookout for interesting field study ideas for her ninth-grade Biology students.

From there, a number of learning opportunities branched out in exciting directions. Fox and the other fourth-grade faculty decided to build a comprehensive inquiry around water for their students, which would include two field trips to the Reppun Farm over the spring semester. Outdoor Education faculty helped the teachers plan experiences that the students could pursue on the farm and how to connect them back to campus. With help from Luke Center, they developed their curriculum using systems thinking to explore water through multiple lenses.

Because water use and preservation is a global issue, Fox reached out to Robyn Borofsky ’99 Vierra, associate director of Wo International Center. Vierra helped to develop an international exploration using virtual reality technology to immerse students in water-related issues of other places: they looked at reef conservation in Indonesia, water treatment issues in Pakistan, and access to water in Ethiopia. The fourth-graders also participated in an exchange project with students in Glasgow who were studying water issues on islands. As the Scottish students researched Hawai’i, Fox’s students created videos to tell them the unique role water plays at Punahou, explained marine debris problems in Hawai’i’s coastal waters, and shared what they learned from the water system at Reppun Farm.

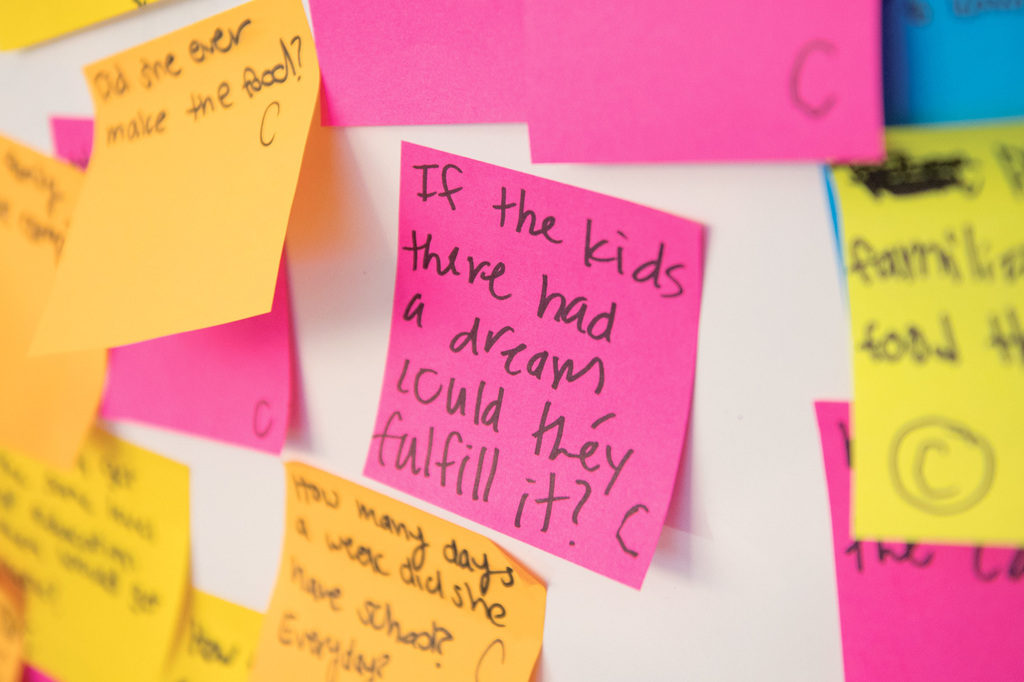

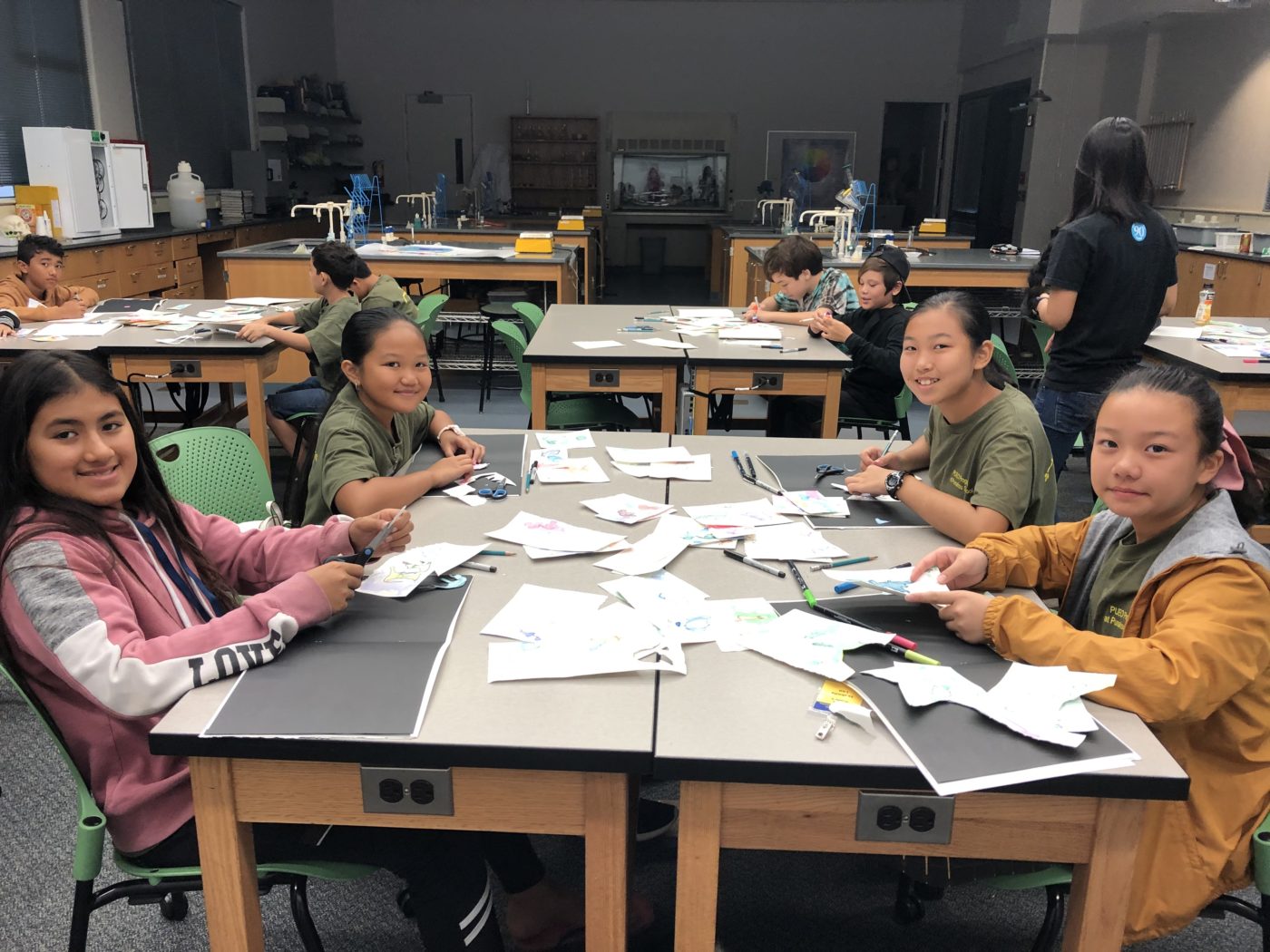

For Marumoto’s ninth-grade students, the visit to the Reppun Farm, where they collected water samples and learned about the farm’s sustainable ecosystem, was a launch pad for their field studies. It was also an opportunity for social, emotional and ethical learning. Each of the ninth-graders was partnered with a fourth-grade buddy for the field trips, and afterward they continued to work with the fourth-graders, guiding them in scientific methods such as centrifuging, doing bacteria counts and comparing their samples from the farm with water from Ka Punahou.

While there was clearly scientific learning taking place, Marumoto says that, “The social-emotional dimension to this class is in some ways more important than the content. We are growing people and I consider myself to be first a teacher of children and second a teacher of biology, so I’m always concerned with how I see students treating each other.” Marumoto says that the buddy experience has been valuable for her students in many ways – including seeing how “the fourth-graders are really curious and willing to make a guess without worrying about being wrong.”

Several of Marumoto’s students were so fascinated by the farm’s water wheel that they chose to make one of their own. To accomplish this, Marumoto asked for guidance from the newly established Design Thinking, Technology and Fabrication department, which recently inaugurated the D. Kenneth Richardson ’48 Learning Lab as a fully-equipped makerspace. Her students worked with the lab’s staff to build a miniature water wheel using 3-D modeling and high-tech machinery. They then used it to measure differences in turbidity in the freshwater stream near one student’s home. Fox’s fourth-grade students also built a water wheel, among other makerspace-inspired projects that the Design Thinking, Technology and Fabrication department facilitated.

A Coordinated Effort

This incredibly rich sequence of events is exactly the type of relevant, interdisciplinary learning that Punahou’s constellation of instructional centers hopes to support. These centers include Wo International Center; Luke Center for Public Service; Kuaihelani Learning Center; Design Thinking, Technology and Fabrication; and Outdoor Education. Luke Center works closely with the School’s longstanding Chapel program around creating instructional opportunities towards community and service.

Although the centers have evolved in a piecemeal fashion over the last 30 years, they have only recently begun to emerge as a coordinated force for facilitating the type of learning expressed by the Aims of a Punahou Education. Each center has a particular area of focus – global education or social entrepreneurship, for example – and they also share a number of instructional values, such as social, emotional and ethical learning, critical and creative thought, and engaged citizenship.

“I get an idea and it tends to be really big,” says Fox. “What’s been great about the folks in the centers is that they stop, listen and help me think about how I can make that idea possible for my students. Every single person in the centers has been more than willing to help and add to the project. No one ever made it seem like it wasn’t possible.”

“I see the centers as these arms of instructional leadership that support students and teachers in realizing the Aims of a Punahou Education,” says Vierra. “They’re organized around the K – 12 Learning Commons as an interdisciplinary hub and that’s the point: Our work is not separate, it’s integrated. Recognizing that in the 21st century, learning is increasingly interdisciplinary, the support for teachers and students needs to be interdisciplinary as well and not siloed.”

Since the beginning of this school year, a number of the centers have received additional staffing and their leadership now meets regularly to better coordinate efforts.

“For me this coordination is creating visibility and building synergy around our shared purpose,” says Dan Kinzer, co-director of Luke Center for Public Service. “It’s a way for us to see the many ways in which our work intersects and how we can optimize our approaches so that students and teachers are having more quality interactions.”

By interfacing with one another on a regular basis, center leaders can ensure that teachers like Fox and Marumoto are finding the help they need to build the ideal learning experiences for their students. Without the focused expertise that each center represents, creating something as rich as the aforementioned water inquiry collaboration might be too time-consuming and complex for a teacher to undertake alone.

A Project with a Purpose

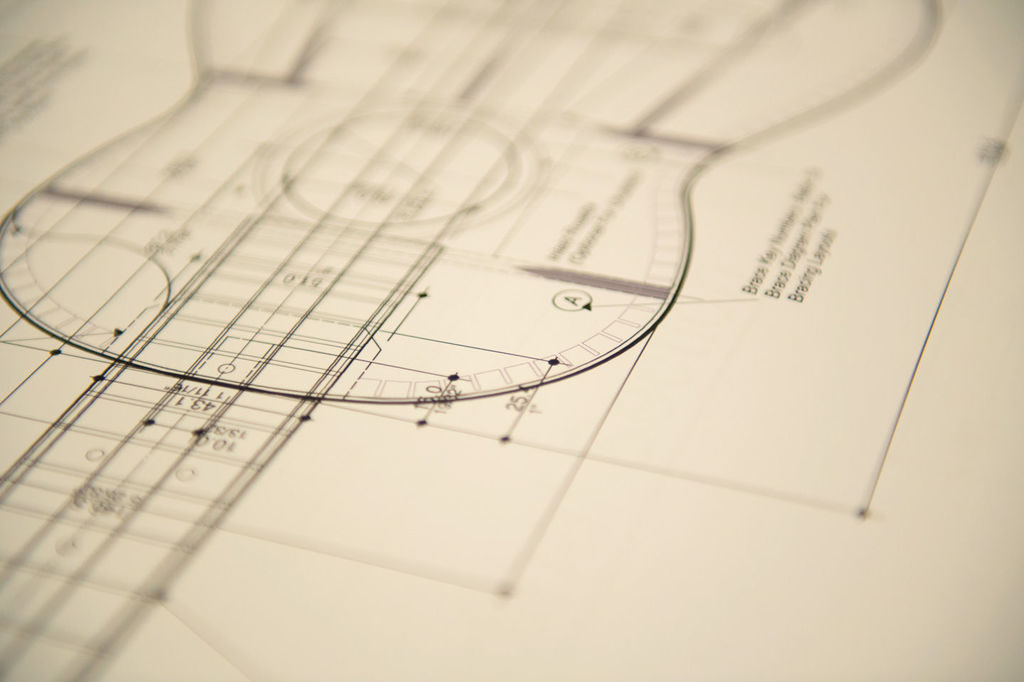

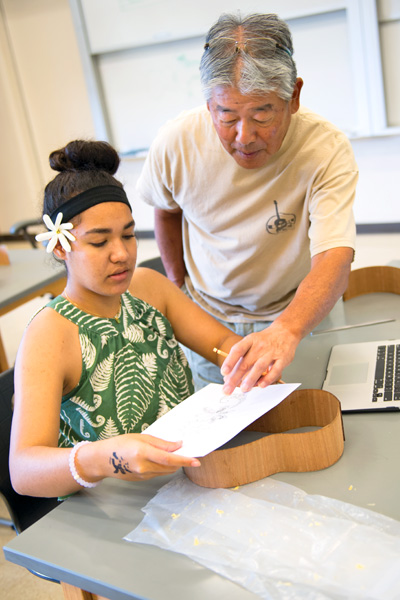

This semester, Academy science faculty Jamey Clarke decided to experiment with more real-world opportunities for his Physics students by asking them to make something for a real audience to supplement concepts they were learning in the course. While they study sound waves, three of his sections are building ‘ukulele with technical support from the Design Thinking staff while having access to the Richardson Learning Lab. The ‘ukulele will be donated to the ‘Ukulele Kids Club, a nonprofit organization that gives the instruments to hospitalized children for music therapy. One of Clarke’s sections is exploring how to build a tiny home in partnership with Hale Mauliola, the homeless shelter on Sand Island that is administered by The Institute for Human Services – giving the project a strong social entrepreneurship slant. The project is being developed in close partnership with Kinzer from Luke Center and Taryn Loveman, co-chair of the Design Thinking, Technology and Fabrication department, as well as Ian Earle ’89, who is advancing Punahou’s curricular sustainability opportunities through a faculty fellowship this year.

In addition to presenting regularly to his students, Clarke says that “Dan, Taryn and Ian have really helped shape that class, which would have never been able to happen with me alone. It would just be way too much for one teacher to do something like this. For example, Taryn has been really helpful in showing how the design thinking process works: As we thought about our tiny home design, we’ve had to establish who our target user is and what their needs are. So rather than just designing what we think they need, we’ve been finding out by researching and talking to people. And those kinds of questions are not ones that I would have known to ask on my own.”

Loveman is a passionate advocate for “kicking down walls” that would normally prevent teachers from developing these types of bold, real-world learning experiences. “We have all the expertise we need right in this group,” he said at a recent meeting of centers’ leadership. “If you’re a student or a teacher and you want to do something, you want to know the quickest way to do it. When you come up with an idea and there’s even two layers of barriers you have to break through – most people will just back off because they can’t afford the time. But those of us here are given the time and we should be trying to make things as simple as possible so that if a student or teacher wants to do something we can say: ‘I have the person for you, I have the space for you, the materials are there, the machines are there, the artist is there, the connection to the community is there – let’s do it. There’s nothing in your way.'”

Different Perspectives

Beyond project-specific collaborations in the classroom, the recent coordination among centers leadership is also leading to interesting cross-pollinations of their work. For example, Loveman and Reppun recently began to translate the design thinking concepts that underlie the Design Thinking, Technology and Fabrication department’s work into a culturally appropriate Hawaiian framework that Kuaihelani can apply to ‘ike Hawai’i, or Hawaiian knowledge. While their centers may seem very different on the surface – Design Thinking, Technology and Fabrication often calls to mind high-tech makerspaces, while people associate Hawaiian culture with history and tradition – they are both committed to nurturing many of the same competencies and mindsets in children as preparation for a rapidly changing, globalized world.

“To me, translating the design cycle into a Hawaiian lens is ultimately about understanding the mindset of the creator,” says Loveman. “We want kids to establish empathy with different cultures and value systems because it helps them understand themselves. When you start to think about other people and what they believe, you reflect on yourself and your own values and beliefs. Even at a very young age you can reach a deep understanding of big ideas like justice and empathy, culture and ecological responsibility.”

Loveman and Reppun discovered through their collaboration that the Hawaiian cultural lens adds two distinct steps to the traditional design cycle: a preliminary phase of seeking inspiration, guidance and correct orientation to a project, and a final phase of gifting or releasing the finished product to the broader community.

“In Hawaiian culture, there’s this assumption that what you’re creating has to have a bigger purpose beyond the self,” says Reppun, “and I think that’s different from a lot of design thinking, at least in the corporate business model. So this cultural lens asks us to think of these other steps as present in the process as well.”

Loveman and Reppun both believe that the more access points to design thinking principles that students have, the more opportunities the School will have to cultivate “the mindset of the creator,” which can be applied to the wide range of challenges they will encounter in the world.

“Innovation is not necessarily synonymous with new,” says Reppun. “When we think about ‘ike Hawai’i, one of the shortcomings is we always think of the past and we miss a huge opportunity to actually bring this knowledge into the present. Part of my mission in Kuaihelani is to flip that idea and make ‘ike Hawai’i relevant to this day and age, to show that it’s applicable to every context in our educational institution and that it can bring depth to the learning that’s happening in all these different spaces.”

Building a Network of Resources

Reppun uses the metaphor of the lehua flower for the work being done through the centers, because there are many buds on a single flower that unfold together when the flower blossoms. “To me, making the centers more robust feels like the move towards 21st-century learning by promoting interdisciplinary learning and this idea of resource teachers who are outside the classroom, who can help facilitate authentic learning through an integration of the expert or practitioner, the classroom teacher and the student experience. I don’t think anybody’s really modeled that well yet.”

All of this is a work-in-progress, say Academy and Junior School principals Emily McCarren and Paris Priore-Kim ’76. The buildout of centers’ leadership and strengthening the connections between them is part of the bigger process of developing a network of instructional spaces that will become part of the K – 12 Learning Commons. While the Learning Commons facilities are still under construction (Junior School) or in planning (Academy), the centers are an obvious place to begin laying the groundwork for the human and physical resources that will sustain this constellation of learning at Punahou.

“We see the most meaningful learning as interdisciplinary,” says McCarren. “Work that is embedded in the real world and connected to things we care deeply about – people, places, cultures, community needs – will inspire us to learn more deeply, ensure that learning endures and ensure that we are able to apply what we learned to different situations in the future. The centers are labs and hubs of innovation in many of the areas that mean the most to us. They teach us about our aspirations as a local, national and global community by providing resources to students and teachers not found in most schools. They are Punahou’s tangible commitment to the rapidly evolving role that education needs to play in our communities.”

Front and Center

Wondering which center does what on campus? Although Punahou’s curricular centers are increasingly working together to further the Aims of a Punahou Education, each one has its own mission and network of resources that allow it to deploy unique expertise to teachers and students across the School.

Luke Center for Public Service

Luke Center supports student entrepreneurship and service learning K – 12, including the School’s many community service and sustainability initiatives.

Kamal Kapadia, Co-director of Luke Center for Public Service

Wo International Center

Wo International Center encourages appreciation of cultural diversity and global responsibility among K – 12 students and faculty, serving as a bridge to the international community and academic institutions worldwide.

Chai Reddy, Director of Wo International Center

Kuaihelani Learning Center

Hawaiian Studies at Punahou educates students about core values and concepts in Hawaiian culture, including an understanding of the School’s deep roots in island history.

Ke’alohi Reppun ’99, Co-director of Hawaiian Studies

Design Thinking, Technology and Fabrication

This department works to fully integrate the design thinking approach to problem solving across a multitude of disciplines at Punahou, making it a core component of the Punahou experience from kindergarten through grade 12.

Taryn Loveman, Co-director of Design Thinking, Technology and Fabrication

Outdoor Education

Punahou’s Outdoor Education program immerses students in experiences that enable them to form a meaningful relationship with the natural world, with a focus on the unique island context of Hawai’i.

Shelby Ho ’01, Junior School Assistant Coordinator of Outdoor Education

Maverick the Duck